Are you pleased?

If you are consistently thrilled with the responsiveness and results of important tasks you assign to your direct reports, there is no need to read on. On the other hand, if you are like the majority of business owners and executives we have worked with, you are probably frustrated at times by the lack of understanding, speed of response and quality of the results of those requests.

If you are consistently thrilled with the responsiveness and results of important tasks you assign to your direct reports, there is no need to read on. On the other hand, if you are like the majority of business owners and executives we have worked with, you are probably frustrated at times by the lack of understanding, speed of response and quality of the results of those requests.

There are two major ingredients to getting what you request done well. The first is Motivation and the second is, what I will call the Assignment Dynamic – which of the two is much more complex but, actually, easier to manage.

Motivation: The Vroom Expectancy Theory

Many books have been written on the subject of motivation, but my favorite model was created by Professor Victor Vroom*, called the Expectancy Theory. It states that people are motivated by the product of three considerations: a) if they attempt something they will accomplish it, b) if they accomplish it there will be a reward and 3) the reward will be relevant to them. If any of these are “zero” there is no motivation. Before giving an assignment, particularly if the assignment is a major challenge, 10 minutes of thought on this motivational model might help,

The Assignment Dynamic:

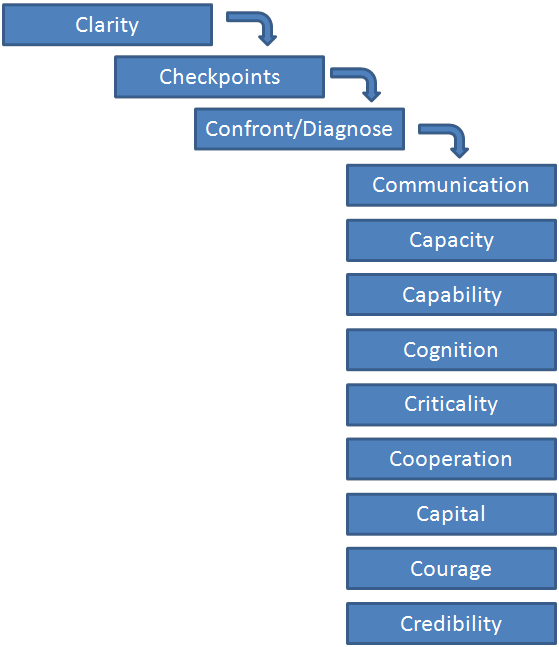

The Assignment Dynamic takes over from the point at which the assignment is given. This Assignment Dynamic is shown in Figure 1. It has 3 major steps. The 3rd step delineates the 9 common barriers to progress.

Figure 1.

1. Clarity: Be clear about what you are asking for. Describe clearly the acceptable form the answer or solution must take. Clarify the timing for the completion, the importance/urgency of the assignment and the priority of the request. If the result is numerical, collaboratively set the number. Just this first step goes a long way in improving outcomes.

2. Checkpoints: Let the individual assigned to the task know you will be checking on progress on a scheduled basis. Set the schedule.

3. Confronting Delays and Diagnosing Barriers: During a checkpoint, if satisfactory progress hasn’t been made, don’t be afraid to confront it. I know, “confront” is such a hash word. In this case, however, “confront” simply means addressing the delay directly and professionally to discover the barrier-to-progress as quickly as possible, rather than simply letting it go with an “OK. I’ll check with you next week.”

The root causes of the lack of progress can almost always be found in the list below. When confronting a delay, discuss directly with the employee the potential barriers to progress. The following 9 items can be used as a barrier identification checklist.

- Communication: Stalls and delays can occur simply because someone failed, or forgot, to tell someone that something had to be done. All of the components mentioned in the section on clarity apply throughout the chain of all the people required to fulfill the request and achieve the goal and an objective is communicated.

Just hours before the attack at Pearl Harbor a small crew manning a newly installed radar site on a mountain near the harbor noticed a large swarm of blips. They did their job by discovering them and thought they had communicated it to headquarters. In actuality, due to breaks, oversights and inefficiencies in the communication chain, the note was not received by the harbor until the day after the attack.

- Capacity: “I’m too busy,” is often the cry for why something is not getting done. In this case, managers must be clear about the priority of the task requested, and if the employee is simply at capacity, be specific about what needs to fall off the tailgate and be delayed in order to make time for this task. Capacity, more often than not, typically means unclear priority.

- Capability: Occasionally an assignment isn’t completed as hoped because employees simply do not know how to accomplish it.

- Criticality: “I just didn’t know it was that important,” is the response to a delay caused by this item. This can be avoided if the first step, “Clarity” is done well.

- Courage: Some people, who have been asked to do something they have never done before, simply do not have the courage to attempt it. Fear of failure, and its consequences, is typically the reason.

- Cooperation: If the employee is unable to elicit cooperation from other employees, departments or customers the manager can assist in breaking free that logjam.

- Capital: Occasionally, funding is needed to enable the completion of a task. If this is the reason for delay, management simply approves the funding or the original task yields its first position to the enabling task of developing the economic justification for the investment.

- Cognition: I don’t understand what you are asking me to do.

- Credibility: Credibility means the person assigned the task doesn’t believe that the task is worthwhile, meaningful or will have the desired outcome.

Here’s a real example: When asked how the economic benefit story for the firm’s new product was being received by customers and the distribution channel, Bill, a lead sales person, said he wasn’t telling the story, because he didn’t believe the numbers. This new product had a compelling economic benefit to customers and the company had collected customer testimonials confirming it. The management was perplexed by this lack of willingness and compliance to tell the economic story to prospects when selling this new product. A little bit of sales person re-education, coaching, clarification and re-explanation of the economic benefit was required to change his belief.

It changed. The result was a 28% increase in sales, in a year when the general economic activity in that sector declined 15%.

Conclusion:

To some, this organized approach to doling out assignments might appear a bit formal and cumbersome. However if the task is truly important, something that really needs to get done, the approach and checklist can prove a very useful tool.

****

Jerry Vieira, CMC is the President and founder of the QMP Group, a Portland, based management consulting firm specializing in marketing & sales organizational transformations. For more information on how to use this Assignment Dynamic model call him at 503-318-696 or email to Jerry@qmpassociates.com.

_________________________________

* In 1964, Victor Vroom developed the Expectancy theory through his study of the motivations behind decision making. His theory is relevant to the study of management. Currently, Vroom is a John G. Searle Professor of Organization and Management at the Yale University School of Management.[4] Source Wikipedia